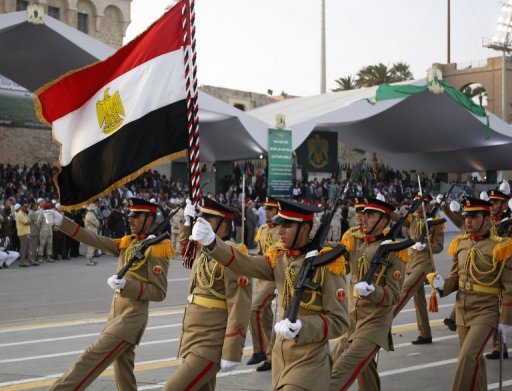

When Mohamed Morsi won the presidential elections in Egypt, a conflict between the president and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) was only a question of time. Morsi’s move to call the Parliament back into session was nothing less than the opening salvo in this conflict and a strong reminder by the President that he, and only he, enjoys a democratic mandate.

But Morsi’s success was by no means foreordained; after all, it was the military that ultimately toppled Mubarak who remains popular among Egyptians and is sometimes even regarded as a stalwart of the democratic transition. Morsi’s attempt to establish full civilian control was bound to run into determined opposition from the military and it seemed likely that the military was aiming for the Turkish model to permanently curb the Muslim Brotherhood’s ambitions. But with the dismissal of Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi and a number of other senior officers about two weeks ago, such a role seems to be out of the question for the moment, even though the military retains its influence over national security and foreign policy. Even more so since Morsi also rejected the supplementary declarations the SCAF issued shortly before Morsi was inaugurated.

But Morsi’s success was by no means foreordained; after all, it was the military that ultimately toppled Mubarak who remains popular among Egyptians and is sometimes even regarded as a stalwart of the democratic transition. Morsi’s attempt to establish full civilian control was bound to run into determined opposition from the military and it seemed likely that the military was aiming for the Turkish model to permanently curb the Muslim Brotherhood’s ambitions. But with the dismissal of Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi and a number of other senior officers about two weeks ago, such a role seems to be out of the question for the moment, even though the military retains its influence over national security and foreign policy. Even more so since Morsi also rejected the supplementary declarations the SCAF issued shortly before Morsi was inaugurated.

The retirement of the entire upper echelon of the Egyptian military was all the more surprising as it arrived on the heels of a military confrontation on the Sinai Peninsula where sixteen Egyptian soldiers were killed in a terrorist attack. The attack marked the onset of a fresh military campaign against radical Islamist networks on the Sinai. The campaign forced Morsi to publicly show his support for the military in their fight against Muslim fundamentalists – the enemy of all Egyptian people. But, at the same time, it was in fact surprising that the Egyptian government had lost control over the Sinai to the extent that it needed a military offensive to re-establish its full authority. Morsi, however, has presented himself as a shrewd politician and saw an opportunity in his apparent dilemma.

“After all, how could the military be the stalwart of the country’s nascent freedom if it failed to perform its most fundamental task – protecting the country?”

But the conflict was never only a political one. It is one of the ironies of the military’s withdrawal of support from the Mubarak regime that it was partly driven by the fear of reforms. For decades, the military had its hand in the till and created an economic empire, with investments in virtually all business sectors, controlling more than thirty percent of the country’s economy. Gamal Mubarak’s rise in the last years of the Mubarak regime was accompanied by economic reforms and these reforms began to undermine the military’s business interests. But younger officers had a different socialisation than the Tantawi generation and had less stake in the military’s economic role. Hence, the Egyptian army lacked the cohesion that would have been necessary to turn it into a single, corrective power in Egypt’s young democracy.

Where does all that leave Egypt’s political scene for now? The current dilemma, in a nutshell, is this: While there is a reason to fear that the military will not allow for democracy to take hold, there is also a reason to suspect that the Muslim Brotherhood might bury the democracy once it is established. But the dilemma gets more complicated when one considers that country still lacks a constitution that could guide civil-military relations and establish the democratic principles that should govern Egypt. For the moment, the Muslim Brotherhood holds a majority in the constitutional assembly, which begs the question whether the emerging system is going to be as secular and democratic as democracy activists—Egypt’s third current and the real revolutionaries—would want it to be.

The retirement of Tantawi and his colleagues was, despite all its political implications, one of pomp and circumstance. And, in the meantime, Morsi made Mahmoud Makki his vice-president, someone who stands for judicial independence. Whatever the outcome of the constitutional assembly, the only safeguard for democracy in Egypt will be a separation of powers, not a continuing guardian temptation.