The recent US-facilitated talks in Madrid mark a significant development in the long-standing Sahara dispute. For the first time in years, Algeria returned to the negotiating table alongside Morocco. The autonomy plan was the only proposal on the table.

This diplomatic shift appears to have immediate reverberations inside Algeria. Notably, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune made no reference to Morocco or the Sahara issue in his most recent televised interview, a striking departure from years of warmongering rhetoric and hate speech against Morocco.

This silence has been interpreted by observers as a sign that Algeria may be preparing its public opinion for a new stance more aligned with the emerging international consensus in favor of the autonomy plan.

Diplomatic sources cited in regional reporting suggest that Algeria’s foreign minister, Ahmed Attaf, who took part in the Madrid talks, requested additional time to formulate an official discourse that could prepare Algerians for a repositioning of the country’s long-standing position.

If confirmed, this would represent an extraordinary reversal after decades of political, financial and military investment in a failed separatist cause led by Algeria’s Polisario proxies.

The pressure on Algiers has grown considerably as global and regional alignments have shifted. Resolution 2797, adopted on 31 October 2025, codifies a major change in the UN’s approach. It explicitly references Morocco’s autonomy plan as the basis for negotiations and rules out the obsolete and unfeasible referendum model, which had long been advocated by Algeria and the Polisario.

This international realignment is reinforced by the growing number of influential states on top of which the US, France, the UK, the EU and most of the Arab World and Africa- including the continent’s major players such as Nigeria and Ethiopia, and influential countries such as Kenya and Ghana – that now openly support Morocco’s territorial integrity and the autonomy proposal.

President Tebboune’s challenge is compounded by his own past rhetoric. Over recent years, he had indulged in anti-Moroccan discourse, often invoking the separatist cause to bolster claims of Algeria’s support for “self-determination.” Yet this principle has been applied selectively, notably denied to the Kabylie independence movement, creating a visible contradiction that has not gone unnoticed by Algerians.

Meanwhile, Algeria’s foreign-policy posture appears increasingly strained. The country has failed to secure entry into BRICS, despite confident public predictions from the presidency. Its relations with key regional actors, including France, Spain, and the Sahel’s AES bloc, are tense or deteriorating.

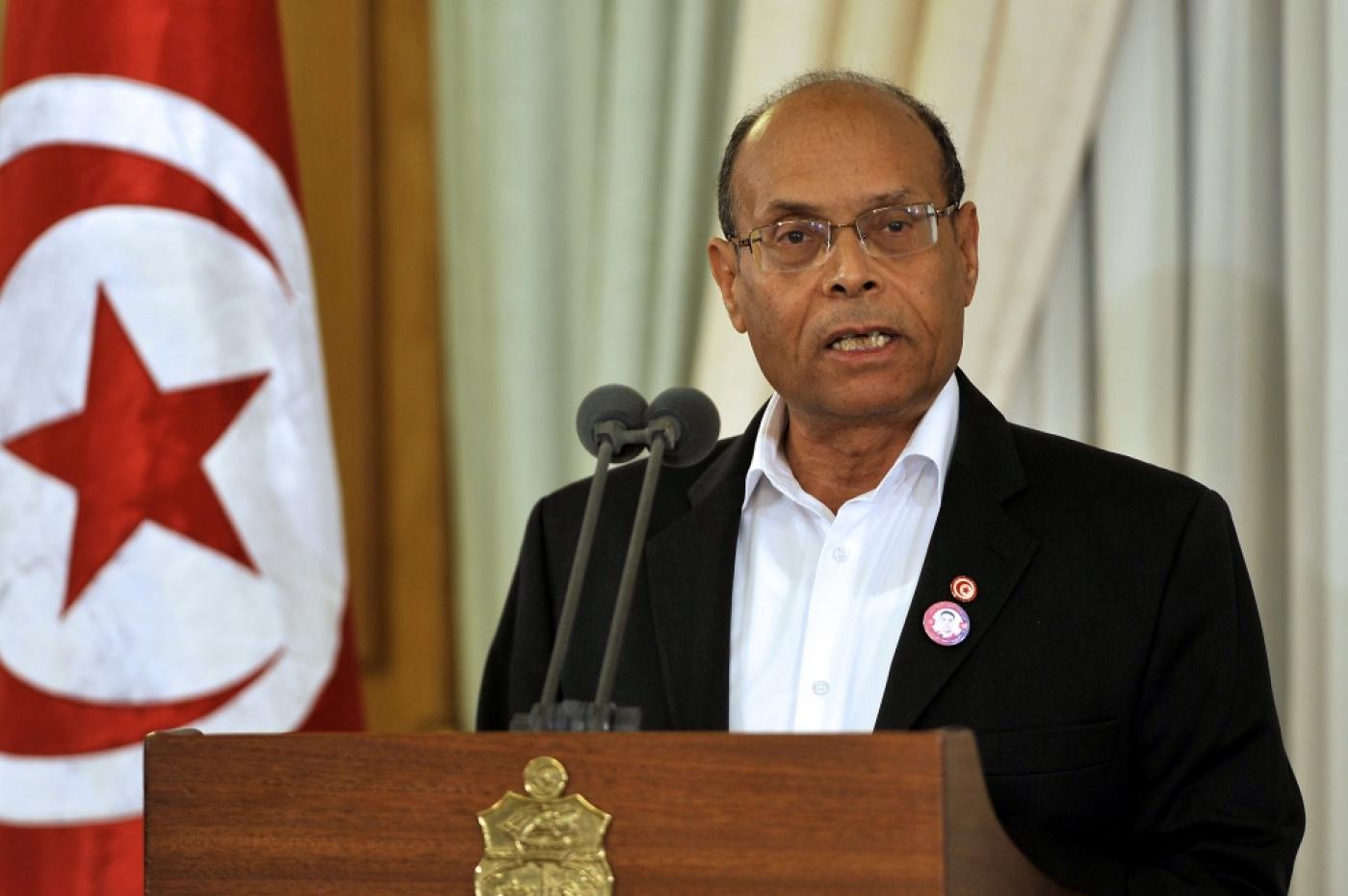

Outside of Tunisia, whose foreign policy has increasingly aligned with Algiers under severe financial dependence, Algeria today finds itself diplomatically isolated both in the Mediterranean and across Africa.

Even within the Arab world, Algeria’s voice has become markedly inaudible as Algiers sides with a weakening Iranian regime and failed authoritarian leaders, the latest of which was Bashar Assad.

Domestically, these diplomatic reversals intersect with Algeria’s deepening economic pressures, including declining hydrocarbon revenues and mounting fiscal constraints. As the legitimacy of Cold War–era narratives wanes among an overwhelmingly young population, the government may find it increasingly difficult to maintain the traditional anti-Morocco posture that has dominated Algerian diplomacy for half a century.

Algeria is now forced or even compelled to lay the groundwork for a historic volte-face. All signs suggest that the foundations of Algeria’s Sahara policy are being quietly but unmistakably re-evaluated.