October 23rd marks the first anniversary of the election of Tunisia’s National Constituent Assembly; the first election since the popular insurrection that brought down the government of President Zine al-Abdine Ben Ali in January 2011and set off the powerful series of events elsewhere in the region that became known as the Arab Spring. The anniversary also represents the opening of the next and possibly crucial phase of Tunisia’s post-revolutionary period of transition as it seeks to put in place a new political system to replace that of the years of dictatorship under Ben Ali and his predecessor Habib Bourguiba.

This phase will see the completion of a new draft constitution for the country and the holding of elections to the new permanent political institutions that this constitution will introduce. If this phase is accomplished without significant upheaval or bloodshed, Tunisia stands to become the first Arab state to have made a full transition from an authoritarian system to a recognisably democratic permanent political system in the wake of the Arab Spring. Despite an apparent consensus across the political spectrum on the objective of establishing a democratic system, there is less agreement on the structure of that system. As political life and debate have blossomed in post-revolutionary Tunisia after decades of tight political control, new ideological and party-political cleavages have inevitably emerged within this apparent democratic consensus.

Last October’s elections to the National Constituent assembly produced a comfortable victory for the Islamist An-Nahda party which finished well ahead of all the other many parties that contested the election. An-Nahda fell short, however, of a majority of both the votes cast and seats in the new Assembly. In the prevailing spirit of post-revolutionary co-operation, two of the other major parties, headed by left-leaning former opponents of the Ben Ali regime, agreed to enter into a coalition with the Islamists to provide a majority for an interim government while the Assembly drew up a new constitution. Like many coalition governments, the new arrangement has witnessed a shaky first year. The dominance of the interim government by An-Nahda members has gone beyond even the lion’s share of ministerial posts that its weight in the coalition merits in the view of many, not least in the two junior coalition partner parties.

Both the Ettakatol and Congress for the Republic (CPR) parties have experienced significant numbers of defections from amongst their deputies in the Assembly as a result of this. As one (still loyal) Ettakatol MP puts it: “An-Nahda has eaten us.” It is a view that seems to be shared by the Tunisian public: recent opinion polls indicate a collapse in levels of public support for both Ettakatol and the CPR. The same polls show that support for An-Nahda, whilst suffering some slippage, remains relatively strong and that it continues to be the single most popular party in the country by some margin. The atomised state of Tunisia’s party political map outside of An-Nahda has, until very recently, meant that the Islamist party has no effective rival and is therefore set to dominate elections to the representative institutions that are to be produced by the forthcoming constitution.

The dominance of the interim government by An-Nahda members has gone beyond even the lion’s share

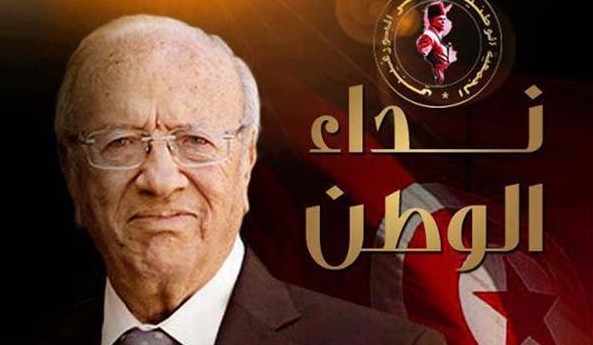

The creation of a new political party over the summer presents, however, a potential challenge to this continued dominance. Nidaa Tounes (The Call of Tunisia), launched in June, which explicitly markets itself as an alternative to An-Nahda, has attracted a number of politicians and figures from other parties and bodies. Most prominent among these is the leader of the party, Beji Caid Essebsi, the interim prime minister who led the government for most of the period between the fall of Ben Ali and the election of the Constituent Assembly last October. A genial and reassuring figure and a charismatic orator, Caid Essebsi is widely admired for the deftness with which he managed the remarkably smooth transition period. This, together with his long experience of ministerial office under Ben Ali’s predecessor as president, Habib Bourguiba, appears to have struck accord with a wide segment of Tunisian society that is uncomfortable with An-Nahda and unimpressed with its management of the government since taking office after last year’s elections. Opinion polls put Nidaa Tounes in a clear second place to An-Nahda.

All of this party political manoeuvring matters given that elections for more long term representative institutions will take place within the year. The collapse in support for An-Nahda’s legislative allies and the rise of Nidaa Tounes raise the very real possibility of the election of a new government that does not feature An-Nahda. Although highly likely to remain the largest party, An-Nahda will probably fall even further short of an overall majority as other parties refuse its invitations to join with them in a coalition government, having witnessed the fate of Ettakatol and the CPR. Nidaa Tounes, by contrast, is already gradually establishing links and securing alliances with other smaller parties in preparation for the creation of a majority coalition government that does not involve An-Nahda.

This prospect has further sharpened already spiky political debate in the country about both the new constitution and politics in general. An-Nahda’s dominance of the interim government has fed the already significant fears amongst large parts of Tunisia’s substantial middle class that the party seeks to impose a conservative Islamist agenda on the country through its presence in the ministries. Appointments of An-Nahda figures to state institutions, radical statements by individual An-Nahda members and deputies, and a perceived failure to confront acts of violence from elements of Tunisia’s small but active and growing salafist movement have heightened these fears and contributed to the growth in support of Nidaa Tounes as a counterweight force.

An-Nahda has defended itself by pointing to the enormous tasks its ministers face in running the country, not least in reforming and replacing the corrupt and problematic aspects and personnel of the former regime. Moreover, it accuses Nidaa Tounes of being a barely concealed front for former regime loyalists seeking a way back into the system. Its perceived failure to deal with the salafist movement reflects, it argues, a desire to avoid boosting the movement through repression and alienation, but it is also less willing to acknowledge its wish to avoid being outflanked by the more radical Islamist message of the movement. An-Nahda accuses secularist elements inside Tunisia of deliberately provoking controversy through provocative works of art and publications to put pressure on An-Nahda which ultimately serve to boost the salafists who can pose as the defenders of Islam if An-Nahda is seen to equivocate.

Nidaa Tounes, by contrast, is already gradually establishing links and securing alliances with other smaller parties in preparation for the creation of a majority coalition government that does not involve An-Nahda

Within the Constituent Assembly, differences between An-Nahda and most of the other parties have emerged over the text of the new constitution and the structure of the new political system it would put in place. An-Nahda deputies proposed a number of socially conservative proposals for the constitution, employing terminology of complementarity rather than full equality to describe men and women’s familial roles and strengthening clauses criminalising blasphemy, which caused huge controversy and were consequently withdrawn from later drafts. On the nature of the new political system, An-Nahda advocates the adoption of a parliamentary system whilst most other parties argue for one with more of a role for an elected president.

An-Nahda claims it wants to avoid creating a presidency that could quickly mutate into the sort of personal dictatorship Tunisia experienced under Ben Ali and Bourguiba. Sceptical observers suggest that An-Nahda is more aware of the advantages that parliamentary systems often give to leading parties in countries such as Britain where a leading party with as little as 36% of the popular vote can win a comfortable parliamentary majority and exercise near absolute power, as Tony Blair and the Labour Party did in the general election of 2005. Much of the leadership of An-Nahda was exiled in Britain during the Ben Ali period. Moreover, Nahda attracted 37% of the popular vote in October 2011. Senior An-Nahda figures have expressed the wish to create a system that delivers majorities rather than coalition governments which it sees as damagingly unstable. The party has, though, stated that it will accept whatever democratic system is more broadly agreed to.

It is unlikely that the text of the new constitution will emerge much before the spring of 2013 and that new elections, either at legislative or presidential level, will occur much before October 2013. A more immediate concern is the make-up of the interim government after October 23rd of this year since its initial mandate was for just a year. An-Nahda argues that the current coalition has electoral legitimacy and should continue whilst other parties say that a new consensus needs to be achieved, possibly bringing in other parties into the existing coalition government.

The implications of all of this are that, although politics remains very fluid and much has yet to be decided, there is a distinct possibility that An-Nahda’s hold on government may be weakened or even ended within the next twelve months. How this outcome would be managed is critical to the stability of Tunisia and the prospects of it creating a genuinely democratic and pluralistic political system. An-Nahda’s critics argue that they fear that the Islamist party will not let go of power easily and might resort to legal and constitutional trickery and possibly violence to keep what they had waited more than three decades to grasp. An-Nahda has, however, consistently stated long before both it came into government and the revolution that it would step aside without protest if it were voted out in a democratic election. It would do so out of respect for democratic principles and processes, which, it also stresses, would additionally protect it – even in opposition – from the onslaught of repression and violence it suffered under Ben Ali’s dictatorship.

The hostility directed at An-Nahda by it enemies in some of the other parties, who most likely would form part of an alternative government, may, however, make it fear reprisals should it ever cede power and would be something that would strengthen the hands of those inside the party inclined not to bow to the will of the electorate. If, however, this change of power is achieved with minimal strife and retaliatory action by the new government, then this would represent a huge and probably decisive step towards the consolidation of democracy in Tunisia.

Much as the victory of socialist parties in France in 1981 and in Spain the following year consolidated and stabilised the French Fifth Republic and the post-Franco democratic system in Spain respectively by showing that change of power – or alternance as the French call it – would not open the way to strife and reprisals. A peaceful ceding of power in Tunisia could have much the same effect on its domestic political scene and the society at large. It would also demonstrate how Islamist parties could be fully accommodated into democratic systems, their willingness to peacefully cede power being as important an indicator of their adherence to democratic norms as their exercise of power when in government.

It should be stated that these political considerations and calculations could all be overshadowed by economic developments. The political drama of post-revolutionary Tunisia has been played out against a backdrop of deteriorating economic and social conditions inside the country. Many of the poorest Tunisians feel that the neglect and marginalisation of the Ben Ali years has simply worsened since the dictator’s departure. The fact that nearly half (47%) of eligible Tunisians did not vote in October 2011 should have sounded more alarm bells than were heard in the political parties. If this disillusionment and marginalisation combines with the growing dismay at rapidly rising prices of food and commodities that hit Tunisia’s poor hard, the complex new politics of post-revolutionary Tunisia could be fully irrelevant as it is swept away by a wave of popular rage and despair flowing in from the impoverished interior and poverty stricken districts of the country’s major towns and cities. This would be a revolution of a much more unpredictable character.

The challenge for Europe is to support in any way it can the continued peaceful evolution of Tunisia’s new political dispensation. The progress it has made so far has been little short of remarkable given the challenges it has faced in seeking to establish the country’s first ever democratic political system. The political divisions and manoeuvring of the transition period may look like troubling instability but more closely resemble the rough-and-tumble of emerging and quite normal democratic politics. Much credit is due to politicians from all sides for constructing a political transition with so little bloodshed and significant levels of compromise and pragmatism. It is to be hoped that the good work that they have done will not be undone by excessive attention being paid by those both within and outside Tunisia to the siren voices coming from the political extremes.