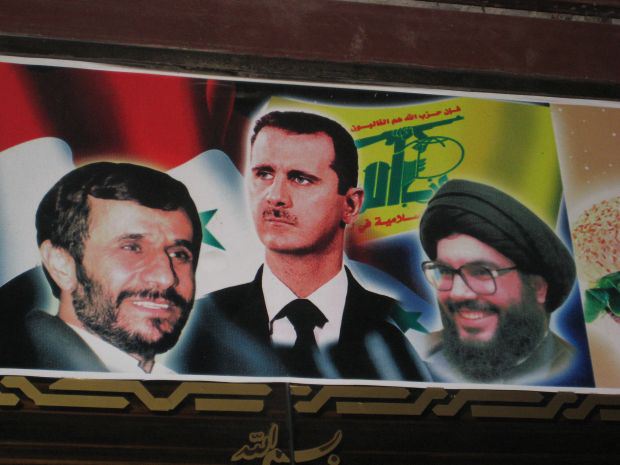

The war in Syria is well into its third year, while the number of casualties has sky-rocketed, though, of course, nobody can say for sure how many lives the war has really claimed. Hezbollah, Iran and Russia have all heavily invested in the survival of the Syrian regime.

Having thus turned the tide of the war in favor of Bashar Assad, the opposition has been looking for international support itself and against the background of a limited Western response has welcomed all the help it could get – even if it came in the form of jihadist fighters who have transformed this war into an at least partially sectarian conflict of Sunni versus Shia. This has provided ample excuse for Western policymakers who want to avoid being dragged into yet another conflict in the Middle East.

Yet, the costs for not responding forcefully to the crisis in Syria have sky-rocketed. The conflict has already claimed thousands of lives and displaced hundreds of thousands, destabilized the region and emboldened the region’s reactionary powers. Still, the dithering of Western powers is likely to continue and even in policy circles and think tanks, policy options are hardly ever articulated clearly, making policy alternatives a variation of murkily formulated nuances. One of the options tentatively put forward and easily dismissed is a military intervention, either as a no-fly zone or in the form of humanitarian safe areas. But since success of such an intervention is uncertain, the case for it is hardly ever made. But the uncertainty of success should not be regarded as sufficient grounds to rule out a course of action, particularly when there are no better options available. It is high time to make the case for a military intervention.

The partially sectarian conflict of Sunni versus Shia has provided ample excuse for Western policymakers who want to avoid being dragged into yet another conflict in the Middle East

Humanitarian Considerations

A couple of weeks ago the United Nations revised its Syrian casualty report to 93.000, while other human rights organizations claim that the number has already surpassed 100.000 deaths. It is an absolute certainty, however, that these 93.000 won’t be the last to die in this war, in which, it ought to be said, much more than just the future of Syria is at stake. The extent of the slaughter and the degree of the human suffering has long made it a moral obligation to stage some sort of humanitarian intervention. After all, when the international community mustered the will to intervene in Libya in 2011 because Muammar Gadhafi was contemplating a massacre in Benghazi, far fewer people had been killed. Gadhafi’s record pales in comparison to what Assad has done to the entire country. What warranted an intervention in Libya two years ago, has long warranted a similar approach to the Syrian regime or else the Western powers in particular will be confronted with applying a double standard – and rightly so.

The Obama-administration realized that the fighting in Syria would sooner or later demand U.S. action. But since Obama had just disengaged from the Middle East, he was hardly keen to get involved in yet another conflict in the region. His administration struggled enormously to come up with a coherent response and declared the use of chemical weapons would constitute a ‘red line’, but he failed to outline what sort of response would crossing that threshold call for. Since it had restricted itself to providing non-lethal assistance only, the use of chemical weapons would not require a military response. Instead, it evaluated the accusations for weeks – long after the United Nations had reported that chemical weapons were used on at least four occasions and France had determined that sarin gas had in fact been employed. It responded by providing small arms and ammunition to the opposition. But in its daily press briefings even the State Department did not want to say whether it considered that delivery to be sufficient. Instead of showing resilience, the ‘red line’ had only demonstrated how little appetite there was for getting involved in the Syrian conflict and had given the Assad-regime an idea with what sort of mass murder he could get away with before Western powers would even begin to think seriously about a meaningful response.

More than 4.000 Hezbollah fighters are reported to be fighting in Syria at the moment, helping defend the entrenched regime

Of course, not all actors in the region acted quite so shyly. A military intervention has long been underway, only that this time it came in the form of Hezbollah fighters, Russian deliveries of arms and Iranian support. More than 4.000 Hezbollah fighters are reported to be fighting in Syria at the moment, helping defend the entrenched regime. Its fighters have taken back rebel strongholds and are now gearing up to re-take Aleppo – an effort that is at least partially bankrolled by Iran, Syria’s staunchest ally. Their tactics are not driven by the desire to avoid civilian casualties, quite the contrary. Such casualties only help deliver the point that Assad wants and in fact needs to make, if he wants to stay in power: that demanding democracy will be paid with blood.

Thanks to the intervention by what must be considered the reactionist alliance of Iran, Russia and Hezbollah, it now looks as if the regime survival is in fact one possible result of the conflict. But given the massive scale of the conflict, a military victory will hardly be enough for the regime to re-gain and consolidate its control. So in trying to re-entrench itself, retaliatory and punitive action by the regime is a certainty, even if the actual fighting comes to an end. The more than 100.000 deaths in Syria are only a fraction of the death toll that would result from an eventual defeat of the opposition. The international community has never defined what constitutes genocide, but it is clear that the fighting in Syria is producing results that come close to meeting its basic criteria.

Not wanting to intervene, Western powers put their hopes in a diplomatic solution. They hope that the Geneva II conference will bring about a negotiated settlement and they have already hinted that they are prepared to accept Assad staying in government one way or the other. But the timing of these efforts could not possibly be worse. With momentum on the side of the regime, the opposition weak and divided and Western powers clearly keen to limit their involvement, there is hardly an incentive for the regime to make concessions.

The United States has made sure to respond to the ‘red line’ the U.S. president had drawn in the most limited way possible. But there is hardly an expert that believes that providing weapons and military equipment to the opposition at this stage is going to tip the balance in the opposition’s favor. The ongoing efforts of Iran, Hezbollah and Russia will not be upended by the influx of more small arms on the side of the opposition. At this stage even the introduction of a no-fly zone might be too little too late.

Strategic Considerations

While humanitarian considerations should provide sufficient grounds for a military intervention, there is also a range of strategic considerations that should call for a far more forceful response to the war in Syria.

While the opposition was facing an uphill battle against the Syrian regime from the moment the conflict ignited, few have doubted that the momentum of the Arab Spring and the record of Assad’s regime would ultimately make his ouster all but inevitable. In fact, it appeared that Assad was intent of leaving office in the style of the former Romanian strongman, Nicolae Ceauşescu. Against this background, it is hardly surprising that not much thought has been given to the question of what an Assad-victory would entail. But it is important to note that it would constitute the first meaningful victory for the reactionary powers in the Middle East since the Arab Spring commenced more than two years ago. As such, it would certainly embolden all conservative forces in the region to avert or at least postpone fundamental reforms and, in a particularly ironic twist, even in those states that support the Syrian opposition, such as Saudi Arabia.

It is in fact troubling how little lessons from past conflicts have been heeded in the context of the Syrian war. Over the past decades virtually all civil wars exhibited a remarkable and troubling tendency to spill across borders – from Bosnia to Rwanda and lately Libya. But nowhere was this as likely as in Syria, where ethnic and religious cleavages cut right through its borders to both Lebanon and Iraq. To say that the fates of Lebanon and Syria are intertwined would be an understatement. The international community has invested heavily in the stability in fragile Lebanon and given the history and extent of Syrian involvement in Lebanese affairs it was an absolute certainty that the longer the conflict in Syria would drag on, the more likely that Lebanon would be pulled into it. Hezbollah’s entry into the war has already expanded the battlefield to parts of Lebanon. By the same token, it is more than likely that Assad-regime would have to consolidate a victory by massive reprisals on Syria’s majority population, sending even more refugees across the border after an eventual end of the war. The consequence would be a massive upsetting of the political balance in Lebanon, hardly a scenario the international community should willingly accept as the price for non-intervention.

Western audiences have noted with delight that the Obama-administration is returning to more traditional realpolitik, abandoning the Bush-doctrine of resilient democracy promotion in the Greater Middle East

The political upheaval that followed the Arab Spring elevated the crises in Egypt, Syria and to a lesser extent of Tunisia and Libya to the forefront of the debate. Yet, the crisis over Iran’s nuclear program is certain to resurface. It would be an equally misleading understatement to assert that negotiations with Tehran over its nuclear program have gone nowhere. Even if these negotiations still have a chance of succeeding, any potentially positive gain by the election of Hassan Rouhani as president of Iran will be offset by its major strategic victory in Syria, if the Assad-regime were to survive. Alas, the Western powers’ failure to act in Syria will only make a military campaign to stop Iran’s nuclear program more likely, provided, of course, that the threat of all options being on the table was ever intended to be taken seriously.

This should bring the debate full circle. After all, there seems to be a consensus that the best way to avoid a war with Iran would be a willingness to contain rather than to confront it. Containment, however, would require a readiness to deal with Iranian influence on its periphery and thus require a strategy to diminish its influence in the region. The fall of Assad would cut the most important lifeline to Hezbollah, which is why the Shi’ite militia has invested so heavily in Assad’s survival. Having secured his regime against Western interests and a domestic uprising would force Assad’s hand to repay the favor in the future: hardly a promising start in any strategy to curtail Iranian influence in the Middle East. And surely not a way to force it into a more compromising stance on the nuclear issue.

Finally, Western powers should have an interest in the opposition succeeding for ideological reasons too. Sure enough, Western audiences have noted with delight that the Obama-administration is returning to more traditional realpolitik, abandoning the Bush-doctrine of resilient democracy promotion in the Greater Middle East. That said, democracy promotion or, to be more precise, safeguarding democratic gains and expanding them, is exactly what the Arab Spring has revealed as a major interest of the, forgive the cliché, Arab Street. So, President Obama’s desire to withdraw from the region, return to realpolitik and pivot to Asia is increasingly at odds with what the historical moment in the Middle East demands. If the West is really worried that weapons might fall into the wrong hands and that jihadist forces might gain too much influence within the opposition, it should stop forfeiting its interests. If it wants Assad gone and gain influence in a post-Assad Syria, it will have to invest.

The Bottom Line

Western nations, from the United States to its European allies, have taken a rather hesitant, at times even a hedging approach to the Syrian crisis. More than two years into the conflict, their strategies – if that is not putting too heavy a burden on the term – have never been driven by the desired outcome of the Syrian crisis. Instead, their approach has been shaped by the desire to limit their involvement, while doing just as little as necessary to keep the opposition from being crushed in a onslaught of air strikes, artillery bombardments and massacres.

With the involvement in Afghanistan winding down and a general fatigue with interventions abroad, it is hardly surprising that Western powers would seek to minimize their responses to the Syrian crisis. But by providing only minimal assistance to the opposition, while catering to domestic opinion, Western capitals have only prolonged the conflict, without changing its course. The result of this ill-fated approach should serve as a rebuke to all that have advocated a hedging approach to the Syrian crisis. This late in the game, even the delivery of weapons is unlikely to alter the fundamental direction of the war.

In fact, the regime remains on the offensive, while the opposition is at its weakest point in the past one and a half years. And without a change in policy, the regime might well survive. Russia can claim to have denied Western powers entry to a country that it considers part and parcel of its Middle Eastern sphere of interest. Its anti-air missiles have provided an umbrella for Assad under which he continues to butcher what is sometimes so callously referred to as “his own people”. At the same time, Iran would strike a major strategic victory by saving its Syrian ally from foreign intervention and a domestic revolution – the first such success for reactionary powers in the wake of the Arab Spring. Such a success for Tehran can hardly be considered an incentive for a more cooperative stance in the Iranian nuclear negotiations.

Sure enough, the specters of Afghanistan and Iraq loom large. But so should Bosnia and Rwanda, conflicts in which the West sat idly by, while hundreds of thousands were raped, tortured and butchered. An intervention might be the only option left to deny reactionary powers a major triumph, though it is still unlikely to find support. Yet, while the failure to intervene might be forgiven by domestic audiences, history does not dish out forgiveness quite so easily.