North and West Africa are facing a complex set of challenges in terms of democratic transition and consolidation, a growing prominence of Islamist influence, and potential knock-on effects of recent socio-political transformations. Adding to this complexity is Africa’s raising geopolitical importance that is evident in the growing interest of other extra-territorial powers, such as China, India and Brazil, for the continent.

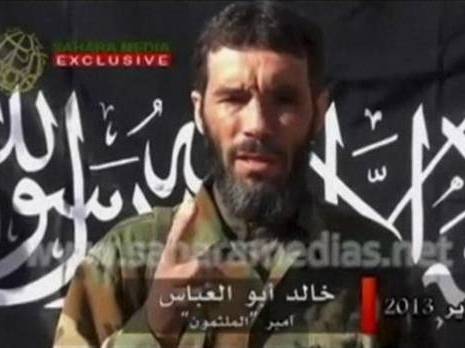

North and West African elites have also demonstrated their willingness to engage with these new partners. But it is failing states or states with a lack of military capacity to uphold order and rule of law – such as Mali – that currently constitute primary security threat for the European Union’s interests because these can create a power vacuum easily filled by militia and terrorist forces hostile to Western modernity, potentially destabilizing wider region.

Since the end of the Cold War that was marked by persistent danger of a conventional all-out armed conflict, strategic thinkers and planners have been increasingly preoccupied by various asymmetric threats. This shift from the emphasis on conventional warfare to the concern over security threats posed by terrorist forces, militias or failing states has been further reinforced following the 11/9 terrorist attacks and the subsequent invasion in Afghanistan and Iraq. But it was the joint EU-US military operations in Libya in 2011 and mainly the latest French-led intervention in Mali that seem to provide a good indication of what lies ahead for the EU foreign and security policy towards Africa. Mali intervention may have offered us a glimpse into the emerging new paradigm of European security thinking and the employment of EU’s hard power that is to primarily draw on small footprint military operations of limited duration.

As Europe’s approach to the civil war in Libya leading to Colonel Gaddafi’s demise has demonstrated, large deployments are over. Moreover, both Libya and Mali have showed us that, in the future, the United States will likely leave Europe to take care of its own backyard lying on its southern flank, while limiting itself to providing a kind of guidance and support – diplomatic, intelligence-sharing and logistical – if necessary and required. Also, rather than attempting to pull together a big alliance, much like the father and son Bush did during the first and second war in Iraq, current leaders will likely prefer to opt for smaller operations conducted by a small coalition of the willing that is more flexible and capable of responding more swiftly to worsening security situation on the ground.

A research project on “Ensuring Peace and Security in Africa: Implementing a New EU-Africa Partnership” conducted in 2009-2011 by the Istituto Affari Internazionali, Chatham House, and the European Union Institute for Security Studies assessed main developments of the Africa-EU relationship on peace and security issues while looking specifically on the comprehensiveness and coherence of the EU’s Africa security policy. One of the main findings is telling: “The EU still does not have a clear definition of its interests in Africa. As a result, the EU has sometimes been perceived as lacking credibility and consistency, in spite of being the largest trade and aid partner in Africa.” Hence, we can question, when looking at the latest French-led military operations in Mali and earlier EU-US actions in Libya, how these are compatible with Europe’s carefully-nurtured image as a mostly normative, civilian soft-power player?

In the wake of the Arab Spring series of uprisings, EU officials rushed to stress that democracy-promotion, empowerment and protection of human security will stand at the centre of future European approach in the Maghreb. Also Catherine Ashton implicitly mentioned that sustainable democratizing is an essential component of European foreign policy in the Maghreb: “When I visited Tunisia and Egypt, I heard several times: this is our country and our Revolution. But also: we need help. These two principles should guide our actions: the democratic transitions have to be home-grown. … But we should be ready to offer our full support, if asked, with creativity and determination… The crisis in Libya and the democratization processes in Tunisia and Egypt will test the EU’s resolve to establish an area of peace and stability in our Mediterranean neighborhood.”

However, even some in Europe question the extent to which the EU has a genuine interest in democracy promotion in the region and also the actual ability of the EU to induce democracy, rule of law and political stability in North and West Africa. Do the EU military missions in Libya and Mali indicate that the Europeans have largely given up on genuine nation-building and democracy-promotion? Will the EU be only interested in conducting limited one-off military operations, designed to prevent the situation from getting out of control, without the aspiration to find long-term solutions to deep-rooted security challenges in the region?

The truth is that nation building is too expensive, both monetarily and politically – no matter whether with or without the lingering euro and economic crisis in Europe. It may be understandable if – mindful of the sobering experience of protracted deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan (not to mention Vietnam several decades earlier) – many policy-makers in the EU favor such a piece-meal, limited approach. But short-term military interventions by themselves are unlikely to resolve the underlying socio-economic problems that have, for example, largely fueled the Islamists’ rise to power – like in the case of Mali. Last, but not the least, also the EU’s credibility is at stake: many accuse it of conducting special operations in Libya and Mali, as part of EU strategy aimed at re-colonization of Africa. More specifically, in light of the growing rivalry between the U.S., France and China in Africa, the assumption is that, while China resorts to economic expansion, the two Western nations rely to a considerable degree on military intervention. Ultimately, what is now needed is EU’s long-term sustainable development policy strategy that would remove the root causes of conflicts and instill long-term stability in the region. The still unfolding situation in Mali has laid bare the fact that Europeans will have to make tough choices about their hard-versus-soft security posture in North and West Africa regions.