Dustin Dehez

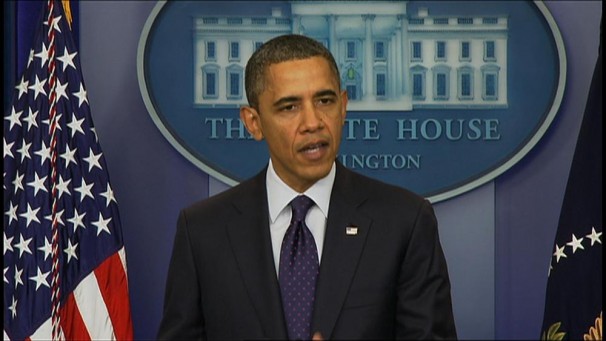

Watching Obama’s second inaugural address, I was confident that the President would turn to foreign policy at some point. After all, Barack Obama has yet to leave his mark on the international stage and his recently announced nominations for his national security team indicated that he was finally thinking about a long-term U.S. foreign policy strategy. As David Ignatius had pointed out, the nominations of Chuck Hagel for Defense, John Kerry for State and John Brennan for CIA make his likely new national security team a team of Obama loyalists.

That is quite a contrast to his first cabinet, where the Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, was a lone holdout from the Bush administration, CIA-director David Petraeus a darling of Republicans and hawkish Democrats, and the Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, his erstwhile staunchest rival. With his cabinet nominations either awaiting Senate confirmation hearings or having just confirmed Mr. Kerry as the new Secretary of State, it looked like Obama was actually creating some cover for a more serious change in U.S. foreign policy.

What is more, virtually all previous presidents used their second term – if one had been granted to them – to do some legacy shopping. Or pushing – to put it differently – some major international initiative that might secure them a place in history. Even George H. W. Bush, who was voted out of office after a single term, used the final days of his White House occupancy to launch Operation Restore Hope, the fateful mission to save hundreds of thousands from a devastating famine in Somalia.

His successor, Bill Clinton, used his final years in office to foster a largely futile peace initiative between Palestinians and Israelis at Camp David. And while his second term was coming to a close, Clinton’s successor George W. Bush was trying to do the same at Annapolis; yet, again failing to reach a breakthrough. It is more than a little tempting to turn to the international arena. After all, the political capital of a second-term president is usually exhausted after a year. And, with mid-term elections coming up in 2014, room for bipartisan compromise will be shrinking at the end of 2013 – while there was not much room for compromise with a Republican-controlled House to begin with.

Against this background, Obama’s second inaugural address was surprising in its combative tone and ambitious domestic agenda. Immigration reform is definitely on the agenda, climate change was mentioned prominently and throughout his address, he made it abundantly clear that – to use Bill Clinton’s words – ‘it is still the economy, stupid’. Obama, however, left little clues as to where his foreign policy is headed. National interests were mentioned only in passing. Other than some generally cautious words on the way in which he will weigh decisions about war and peace, there was not even a slight hint what might eventually constitute an Obama-doctrine or a U.S. grand strategy.

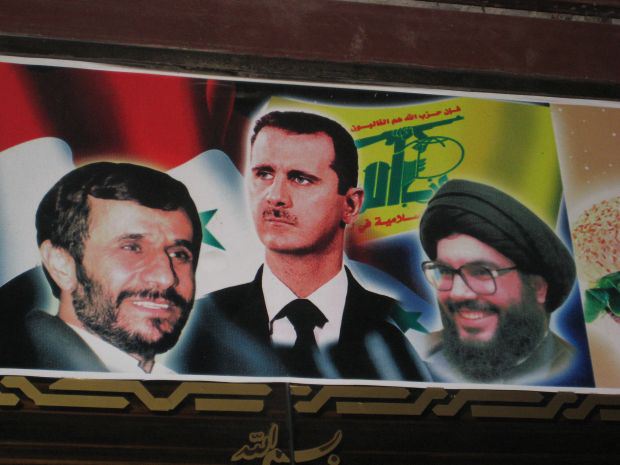

That is slightly odd considering that the to-do list is getting longer by the day. U.S. relations to Russia are in disarray, there is still no comprehensive strategy toward Africa and Latin America, let alone Afghanistan and Pakistan, and there is still no coherent policy approach toward the Middle East and North Africa – a region experiencing historical changes that will determine in all likelihood the fate of democracy in that region for decades to come, which is a long-term interest of a still indispensable nation that cannot disentangle itself from the Middle East and the Maghreb whether it wants to or not.

Obama’s second inaugural speech showed first and foremost that, at least for the time being, his agenda remains primarily a domestic one. And though this agenda is quite ambitious, history is hardly going to give him the room he needs to accomplish all he has set out to do. International events will intervene sooner rather than later. The earlier his administration begins formulating a strategy, the earlier he might actually secure his place in the history books. Coming back to the North African region it was, in the end, the Arab Spring that served as a powerful reminder that not all politics, after all, is local.

Watching Obama’s second inaugural address, I was confident that the President would turn to foreign policy at some point. After all, Barack Obama has yet to leave his mark on the international stage and his recently announced nominations for his national security team indicated that he was finally thinking about a long-term U.S. foreign policy strategy. As David Ignatius had pointed out, the nominations of Chuck Hagel for Defense, John Kerry for State and John Brennan for CIA make his likely new national security team a team of Obama loyalists.

Watching Obama’s second inaugural address, I was confident that the President would turn to foreign policy at some point. After all, Barack Obama has yet to leave his mark on the international stage and his recently announced nominations for his national security team indicated that he was finally thinking about a long-term U.S. foreign policy strategy. As David Ignatius had pointed out, the nominations of Chuck Hagel for Defense, John Kerry for State and John Brennan for CIA make his likely new national security team a team of Obama loyalists.

Watching Obama’s second inaugural address, I was confident that the President would turn to foreign policy at some point. After all, Barack Obama has yet to leave his mark on the international stage and his recently announced nominations for his national security team indicated that he was finally thinking about a long-term U.S. foreign policy strategy. As David Ignatius had pointed out, the nominations of Chuck Hagel for Defense, John Kerry for State and John Brennan for CIA make his likely new national security team a team of Obama loyalists.

Watching Obama’s second inaugural address, I was confident that the President would turn to foreign policy at some point. After all, Barack Obama has yet to leave his mark on the international stage and his recently announced nominations for his national security team indicated that he was finally thinking about a long-term U.S. foreign policy strategy. As David Ignatius had pointed out, the nominations of Chuck Hagel for Defense, John Kerry for State and John Brennan for CIA make his likely new national security team a team of Obama loyalists.