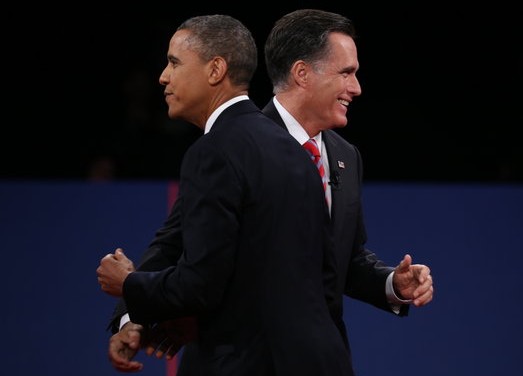

The US elections and the monotonous presidential debates bear little to no substance on North Africa. In the much-anticipated third debate on foreign policy, there was scant mention of the countries of the Maghreb and their important strategic worth in US global fight against terrorism. Except for Libya (mentioned 12 times) in the context of the murder of US ambassador Chris Stevens, president Obama mentioned Tunisia once in passing. This is the same Tunisia where the catalyst behind the so-called “Arab spring” was born.

The Maghreb has long been a region forgotten and detached from the rest of the Middle East in US foreign policy making. However, recent events in the past few months have made it a necessity for the US to integrate the region in its regional assessment. The ever-changing nature of state-society relations in the region amidst the Arab awakening and the increasing threat of extremist Islamist influence in the southern borders of the Maghreb along the Sahel region are two crucial strategic concerns for the US.

Each of the five countries of the Maghreb feature a set of authoritarian challenges that have to be incorporated in a general “Democracy Agenda” that the US has to pursue now, more than ever before, in the context of the Arab street movement for change.

The political challenges facing the Maghreb region reflect the current Arab plight of the persistence of authoritarianism, economic backwardness and the rise of radical Islamism. Each of the five countries of the Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and Mauritania) feature a set of authoritarian challenges that have to be incorporated in a general “Democracy Agenda” that the US has to pursue now, more than ever before, in the context of the Arab street movement for change. A cursory look at each of the Maghreb states reveals tremendous challenges for US foreign policy making.

Algeria is beset by an autocratic state dominated by the military, state security services, and rampant corrupt clientelistic political elite. Although the regime has survived the civil strife of the 1990s, the state never fully addressed the causes behind the Islamist insurgency, namely the prevalence of patrimonial practices and the lack of political accountability. The state in Algeria also tightened its control of political contestation, as it banned the Islamist group the Islamist Salvation Front (FIS) and has curtailed the space for political participation for other opposition parties.

Morocco features some strategies of state political manipulation and stagnant reform agenda. State strategies have resulted in the relative ineffectiveness of proposed political reforms and the weakening of the major political opposition groups in the kingdom. The two main Islamist movements of Justice and Development (PJD) and Justice and Charity share a highly popular agenda of social, political and economic reforms. Despite the PJD electoral success in last November’s elections, it has since morphed into a loyal palace party functioning at the whim of the king’s vast executive prerogatives. Gone are the days where the PJD, formerly the largest Islamist opposition party in the Moroccan parliament, pursued a policy of political dissent seeking governmental accountability and transparency. The passage of the new constitution has gone only some way to guarantee a steady movement towards democratic progress in Morocco.

While Algeria and Morocco still languish, to various degrees, under the yoke of authoritarian rule, Tunisia and Libya have each in differing ways toppled their despots, but still face important challenges. The announcement of the general elections in Tunisia next June will certainly be a test for the consolidation of peaceful contestation of power. The last few months have seen a stark division between the Islamist camp led by the ruling government of Ennahda, and the secularists led by the ceremonial president Moncef Marzouki. Tunisia’s predicament lies in the ability of Ennahda to tame, or perhaps distance itself, from Salafi groups that long for a return to strict Islamic laws in politics and society.

A year after the historical elections in Tunisia, the Ennahda-led government’s record is mixed. A recent Amnesty International report decried the failure of the government to “fully outlaw discrimination against women,” the disproportionate, “unnecessary and excessive force” used by security forces and the lack of a fully functional and independent judiciary. The report came amid fervent protests after the death of an opposition politician, Lotfi Nakdh, in clashes between pro-and anti-government supporters last week.

Libya is perhaps more of a concern as the central government in Tripoli has little influence over the rest of the country. The murder of the US Ambassador crystallizes the creeping lawlessness in Libya. With the tribes of Bani Walid still in revolt and the general lack of security, Libya’s path towards political and societal progress may still be a function of the ability of state to extend its central control. Toppling Qaddafi has come at a dire cost for the region. Spillover arms and ammunitions have found their way to northern Mail where “al-Qaedist” ‘Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa’ (MOJWA) and Ansar ad-Dine have taken effective control of the area and imposed a stricter interpretation of the Shari’a law.

Finally, Mauritania is firmly under the control of a military junta, which staged two coups since 2005. The second putsch of 6th August 2008 put a stop to the promising civilian presidency of Sidi Ould Cheikh Abdallahi. Elected through fair and free elections, Abdallahi showed deep commitment to democratic reforms. Soon, his ambitions would clash with the military that toppled Abdallahi amidst economic hardship and increasing social unrest. Needless to say, the future of political reforms in the country is ambiguous at this point, amidst the “accidental” shooting of its current strong man Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz.

The new US administration needs to further press for good governance, rule of law and accountability in order to increase the scope of individual and group liberties.

Given the current political climate, US foreign policy needs to address the political challenges facing the Maghreb region, in the contest of a vibrant “freedom agenda” that would promote meaningful reforms. The new US administration needs to further press for good governance, rule of law and accountability in order to increase the scope of individual and group liberties. The relevance of the region to US foreign policy is intrinsically linked to a successful resolution of the Western Sahara conflict, which continues to stand as an albatross for regional cooperation. Furthermore, the region cannot be ignored by the international community especially within the context of the threat of terrorism in the Maghreb and the Sahel regions. Terrorist acts have increased in the Maghreb generally since 9/11, but especially after the collapses of Qaddafi’s regime and Malian central governmental control over the north of the country.

Governor Romney, to his credit, mentioned this particular threat in reference to Mali, but the US has thus far exerted no urgency in the region as Iran’s nuclear ambitions continue to be the cause célèbre for US foreign policy. It is incumbent upon the US to logistically assist the countries in the region in combatting the threat of radical militant Islamism. Joint US-Maghrebi exercises on counter-terrorism tactics could greatly help reduce or neutralize the threat of al-Qaeda-affiliated groups in the region. Economically, the U.S. should also seek engagement of the region through a broader Maghreb-US-EU partnership that would further economic growth and political reforms.