The widely-circulated US daily New York Times painted a very bleak picture of the situation in Algeria, where signals for a new dawn are fading away, and where the system renews itself ceaselessly and refuses to change.

The widely-circulated US daily New York Times painted a very bleak picture of the situation in Algeria, where signals for a new dawn are fading away, and where the system renews itself ceaselessly and refuses to change.

The revolt in the streets that began last year, known as Hirak, initially appeared to signal a new dawn in a country that had been stifled for decades by its huge military. But, after the protest movement’s failure to coalesce around leaders and agree on goals created a vacuum, the remnants of the repressive Algerian state, with its ample security services, stepped in, the daily states in a long article entitled “hopes fade for new political course a year after popular uprising”.

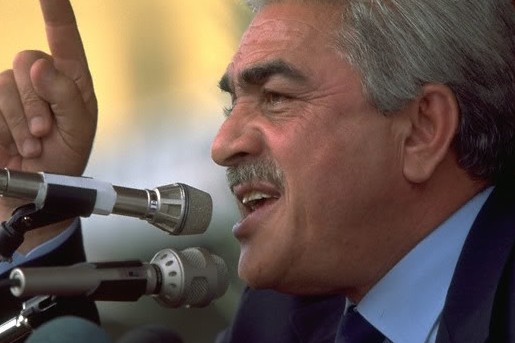

A year after the popular uprising ousted the former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, and led the army to jail much of his ruling oligarchy, hopes are now fading for an overhaul of the political system and real democracy in Algeria, wrote the paper’s Paris bureau chief Adam Nossiter who traveled to Algiers to interview the current president.

“Old habits die hard in this North African country, which has known nearly 60 years of repression, military meddling, rigged elections and very little democracy,” wrote the paper, recalling that the military established its pre-eminence in politics shortly after the country’s independence, and has been at the forefront or just behind it ever since.

The president insisted in the interview that his country was now “free and democratic,” but the NYT’s reporter recalls that it is within this same old, corrupt system that the current President, elected in a vote that opponents said drew less than 10 percent of the electorate, had spent his entire career. Decades of history are not so easily reversed.

“Today there are two political narratives in Algeria: the one from the President, on high, and the one in the streets below,” noted the paper, adding that the coronavirus pandemic stopped the demonstrations in March, and since then the government has played a cat-and-mouse game with Hirak’s remnants, releasing some and arresting others.

In this connection, the author of the article pointed out that the state jails dissidents, mentioning the arrest and prosecution, for “endangering national unity”, of journalist Khaled Drareni, 40, who condemned the system that renews itself ceaselessly and refuses to change.

In addition to growing repression, the journalist mentioned corruption, rigging, and fraud in parliamentary elections. “Seats have been for sale — the going price was about $540,000 according to a parliamentarian’s court testimony — in the same Parliament that ratified the president’s proposed new Constitution, drafted after he came to power in a disputed election in December.”

Caught in the middle are ordinary Algerians — skeptical of the new President’s claims of renewal and of his new Constitution, deflated by the demise of Hirak and angry about the imprisoned Mr. Drareni.

The activists who took a leading role have refused to engage with the deposed leader’s heirs, including the new president.

And for all the talk of a new Algeria, the president employed the old language of the autocrat when he discussed dealing with dissent.

He spoke of change, vaunting his new Constitution, which limits a president to two terms and recognizes the rights of the opposition, at least in the eyes of its supporters. But this past week, the government threatened to strip Mohcine Belabbas, an opposition politician who played a major role in the Hirak, of his parliamentary immunity.

“We are moving backward fast,” Mohcine Belabbas told the NYT’s journalist.