The fossils discovered in a Moroccan cave are about 773,000 years old, filling a critical gap in the understanding how human beings came to be. The finding upends theories on early human evolution, said new research published in scientific journal “Nature”.

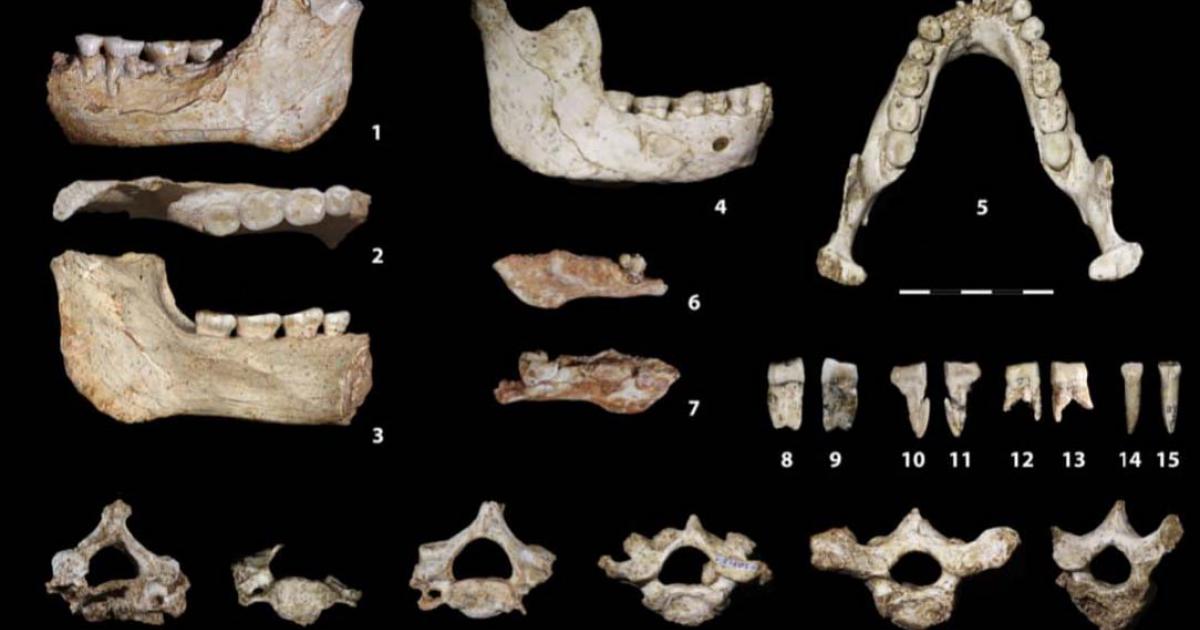

The Moroccan fossils, a mandible, or lower jawbone and other remains, of a hominin specimen named ThI-GH-10717, were found during excavation in the Thomas Quarry. They help close a gap in Africa’s fossil record of human origins.

For decades, researchers have turned to the fossil record of the Middle Pleistocene age in search of the lineage from which both modern humans and their close relatives on the evolutionary tree, the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) and Denisovans, emerged.

“We can say that the shared ancestry between these three species is perhaps in Grotte à Hominidés in Casablanca,” says study co-author Abderrahim Mohib, a prehistorian at the National Institute of Archaeology and Heritage Sciences in Rabat, Morocco.

The cave is part of a quarry, where the first mandible was discovered in 1969. Another adult mandible and a string of vertebrae turned up in 2008, and part of a child’s mandible was unearthed in 2009. The hominin bones and animal remains make up an assemblage of fossils that appear to come from the den of a carnivore, perhaps a hyena. Among them, a hominin femur that was excavated from the cave bears teeth marks.

Researchers couldn’t make much of this steady drip of hominin fossils until they figured out how old they were. The key to pinning that down was a method called magnetostratigraphy, says Serena Perini, one of the study authors and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Milan.

This method depends on the fact that Earth’s magnetic field flip-flops every few hundred thousand years. The polarity change can be detected in iron-rich minerals. There was a reversal 773,000 years ago, which allowed the researchers to pinpoint when the sediments surrounding the hominin fossils were laid down.

As to who the hominin bones belonged to, tiny anatomical features on them point to an in-between species—one with some traits that were reminiscent of older African hominin species such as Homo erectus and others that were similar to those seen in later African fossils and specimens from Eurasia, Mohib says.

This suggests that the Moroccan fossils represent something of an in-between species. They’re similar in age to a Neandertal-like species from Spain called Homo antecessor that had previously been suggested as a possible common ancestor of modern humans, Neandertals and Denisovans.

“They display a combination of primitive and more advanced traits, indicating human populations close to this phase of divergence,” Mohib says. “They thus confirm the deep antiquity of our species’ African roots and highlight North Africa’s key role in the major stages of human evolution.”

These ancestors may have looked quite different from any of these three human lineages, says Antonio Rosas González, a paleoanthropologist at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Spain, who was not involved in the research.

These results illuminate African populations substantially predating the oldest Homo sapiens fossils discovered at Jebel Irhoud, also in Morocco, dated to 300,000 years ago. They constitute solid proof of an ancestral African lineage to our species. Paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin, the study’s principal author, notes these discoveries fill a “gap in the African fossil record” concerning this key human evolution period.