The human slave auction documented by CNN in Libya ignited global outrage and drew attention to an inhuman practice that is regrettably also rampant in other parts of Africa where the media does not have the freedom to report on abhorrent slavery practices.

The human slave auction documented by CNN in Libya ignited global outrage and drew attention to an inhuman practice that is regrettably also rampant in other parts of Africa where the media does not have the freedom to report on abhorrent slavery practices.

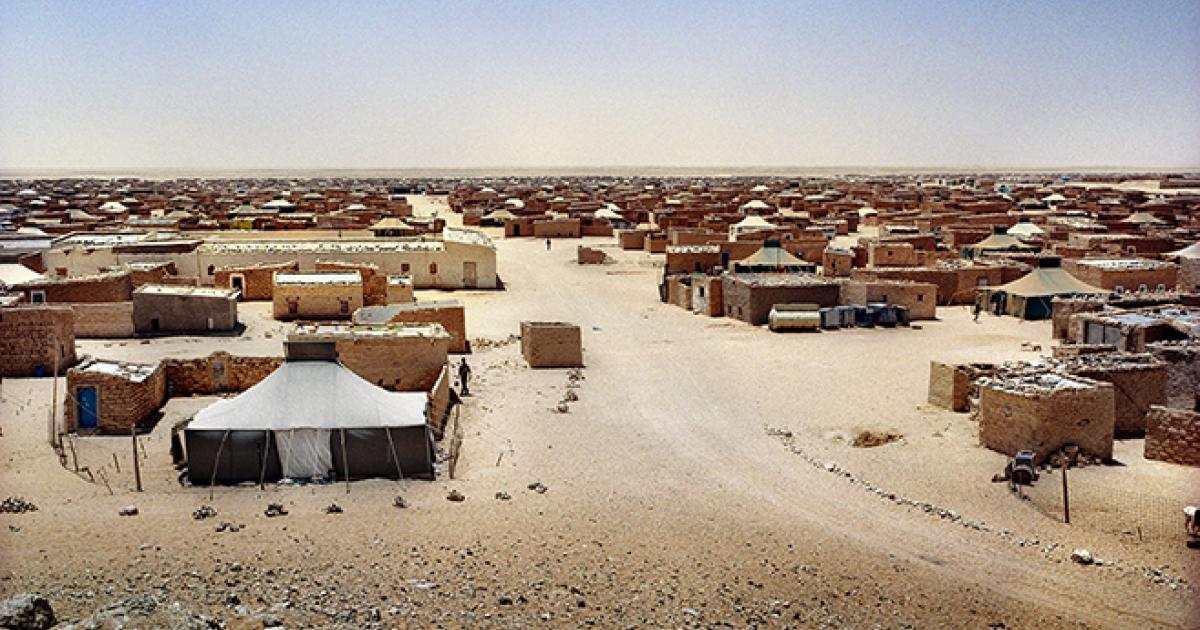

The wave of condemnation of degrading treatment endured by sub-Saharan migrants reduced to slavery in Libya was largely an outcome of the mediatization of the auction, unlike the ordeal of the black population in Tindouf, which continues because of the media-black out imposed by the Polisario leadership and their mentor Algeria.

If slavery in Libya as an outcome of the erosion of the rule of law in a war-torn country, human auctions in Tindouf is an institutionalized practice that is a relic of an archaic tribal system. In these camps, slave masters hold documents attesting to their “ownership” of other human beings, mostly blacks.

In 2009, two Australian journalists with the Sydney Morning Herald were invited to the Tindouf camps by the Polisario representative in Australia with the aim to carry out a propaganda coverage in favor of the Polisario leadership.

However, once in the camps the two journalists noticed slavery practices and decided to secretly film a documentary on the ordeal of black people in the camps.

The film, dubbed “Stolen”, exposes modern-day slavery in the refugee camps of Tindouf through telling the story of a Sahrawi girl called Fatim Sellami, herself a slave, who was reunited with her mother after 35 years of separation with the help of the United Nations.

The film, which also tackles several cases other than Fatim’s, was not initially meant to deal with slavery. Ayala and Fallshaw wanted to make a documentary on the living conditions in the Tindouf camps, but when they arrived there, they found out about the slave trade and decided to shift focus.

The film shows that those Sahrawi girls offered for sale are persecuted and are frequently beaten. Their names are also changed and they are not allowed to marry except with the permission of their masters who have to provide them with a document stating that they have been granted freedom.

In its annual report on the human rights conditions in the Tindouf camps, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has condemned the persistence of slavery practices.

“Practices of slavery that centuries ago were a basic feature of traditional nomadic culture in the Western Sahara appear all but nonexistent among the Sahrawi refugees today,” HRW said in its report on Tindouf camps.

“The persistence of certain forms of slavery highlights the need for continuous, on-the-ground human rights monitoring,” HRW said.