Algeria, Africa’s largest country, shares borders with 6 countries, all of them are closed with the exception of its land frontiers with Tunisia. This closed-border attitude is reflective of a lack of a neighborhood policy in an increasingly integrated continent where collective efforts are the best means to countering trans-border challenges.

Algeria, Africa’s largest country, shares borders with 6 countries, all of them are closed with the exception of its land frontiers with Tunisia. This closed-border attitude is reflective of a lack of a neighborhood policy in an increasingly integrated continent where collective efforts are the best means to countering trans-border challenges.

With Morocco, the borders have been closed following a unilateral decision by the Algerian regime in 1994 in response to Morocco’s decision to impose visa on Algerian citizens out of security concerns in the wake of an attack on a hotel in Marrakech, at a time Algeria was mired in a bloody civil war.

Sealing the borders from the Algerian side persisted since then despite official calls from Morocco to normalize ties and regardless of the fact that Morocco unilaterally lifted the visa requirements for Algerian nationals in 2006.

Although the Algerian regime justifies the closure of the borders with a quest to fight cannabis trafficking, the deep causes for keeping them sealed lies in Algeria’s schemes to contain Morocco and keep it in check. Algerian officials who continue to be hostage to a cold war mentality think that opening the borders will be more beneficial for Morocco, which has an attractive tourist market luring Algerian tourists. They also think that the free movement of goods will mostly benefit Morocco, which has a free market and a more competitive industry in contrast to Algeria’s full dependency on hydrocarbons as a source of revenue.

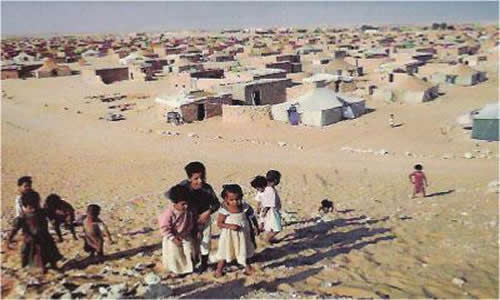

The hidden agenda behind closing the borders with Morocco was an illusion nurtured by the Algerian regime that the Kingdom will succumb to their oil-funded hegemonic schemes in the region. Algeria, which hosts, arms and funds the separatist Polisario militia, has made of isolating Morocco the supreme goal of its diplomacy.

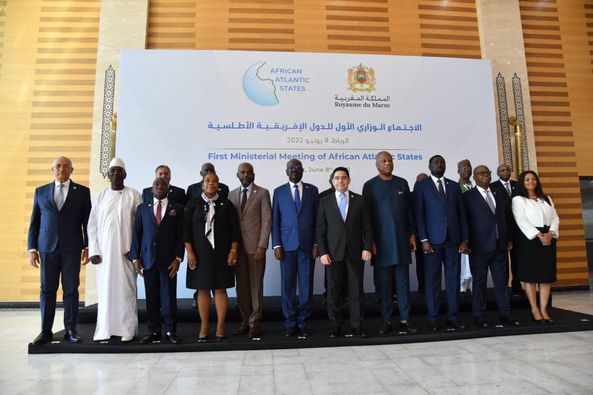

To their disappointment, that strategy is eroding in the face of the economic and diplomatic inroads made by Morocco with a return to the African Union and an increasing support by countries that once were ardent defenders of the Algerian-nurtured separatist thesis in the Sahara. These countries include heavy weights such as Nigeria and Ethiopia as well as influential countries in terms of economic performance in the continent and democracy such as Rwanda and Tanzania.

Algeria’s strategy to isolate Morocco has backfired. The zero sum game evinced by the Algerian regime regarding regional integration and rapprochement with Morocco kept the Maghreb in a state of limbo leaving the Kingdom with the only choice of seeking regional integration with its southern neighbors, precisely the ECOWAS where the Kingdom’s banks and companies have been operating for years.

A look at Algeria’s other borders with the Sahel countries, namely Mauritania, Mali and Niger, shows that the country is cutting itself off a region where it aspires to be a “regional leader”. With Mauritania, Algeria has closed its borders and Nouakchott responded by declaring the border area a military zone forbidden to civilians. With Mali and Niger, Algeria sealed its borders for security reasons, preventing Touareg communities from the freedom of movement in their ancestral lands.

Using the security issue to prevent the freedom of movement of people and goods in the region is flawed. Fighting terrorism in the region should be a collective endeavor as national approaches have long proved their inefficiency. Yet, there is a silently brewing lack of trust between Sahel countries and Algeria on the issue of terrorism. Algeria, the native land of the leaders of most terrorist groups operating in the Sahel, has shown ambivalence in tackling the terrorist threats, which feeds suspicions and erodes trust in Algeria’s willingness to combat terrorism.

The connivance of Algeria’s intelligence services with Algerian national Moukhtar Belmoukhtar, aka Mr Marlboro, is no secret. International reports have also accused Algeria of cooperating with Ansar Eddine and its leader Ag Ghali to quell the separatist ambitions of the secular Azawad movement. Algeria’s support for Ag Ghali was intended to foster extremism in the region to avert a spillover of an independent Tuareg state on its own Tuareg population.

Algeria’s laxism with Ag Ghali facilitated the merger of four terrorist groups operating in the Sahel into one group pledging allegiance to Al Qaeda and its Jordanian leader Azarkawi. The four terrorist groups were brought together under the command of Ag Ghali. The new terrorist organization bears the name of “Jamaât Nasr Al islam wa Al mouminin” (Group for the Defense of Islam and the Muslims).

The creation of the G5 has also infuriated Algerian political leaders. It is no coincidence that the anti-Sub-Saharan migrant rhetoric is on the surge following the formation of the G5 force.

While it prides itself of being the Mecca of Revolutionaries, Algeria has later adopted the attitudes of the colonizer in dealing with Sub-Saharans. Anti-migrant rhetoric verging on blatant racism is uttered by senior officials who come to shamefully associate illnesses, AIDs and economic hardships with the arrival of a few thousands of poor Sub-Saharans fleeing difficult conditions and conflict.

The antagonism of Algerian officials makes them myopic to the changes experienced in Africa. As the legitimacy of the Algerian regime erodes at home, its ideological alliances built on generous oil money handouts are gradually dismantled in the continent, since Africa lives in a new dawn where genuine win-win partnerships, technology transfer and investments are the best way to strengthen bilateral relations.