France’s Persistent Role in Africa: The Other ‘Indispensable Nation’?

While recently attending a conference in Benin, the crisis in Mali still loomed large. The conflict in Mali had threatened to unravel the entire security situation in the Sahel and Western African nations spent much of the last year bickering whether a military intervention to save Bamako from approaching Islamist militias was feasible.

In the face of Western African foot-dragging, the beleaguered government in Bamako turned to Paris. The French soon launched Operation Serval and drove the rebellion back to north-eastern Mali, where it had started. Sitting in a Cotonou conference room and listening to often self-congratulatory accounts of African successes, even West African diplomats still called the French intervention bold and courageous and did not struggle long to admit that it was also a necessity to save the Sahel from an otherwise greater doom.

France always had a special relationship with Africa and that relationship persisted even after the end of the Cold War

Yet, outside Western Africa, many observers called it a neo-colonial enterprise, a thinly veiled attempt to secure French economic interests. Apparently, to many Western observers, even the formal invitation – or, to be more precise, desperate plea – of a sovereign African government for assistance cannot make a European led intervention anything other than an exercise in imperialism. This has led to an awkward reverse-colonialism, where European observers often excel in anti-colonialism, even if they do so at the expense of the very African countries with which they profess to express solidarity.

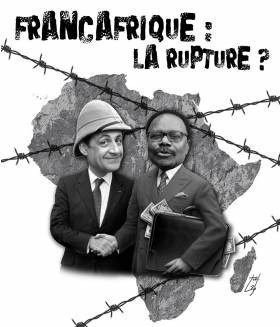

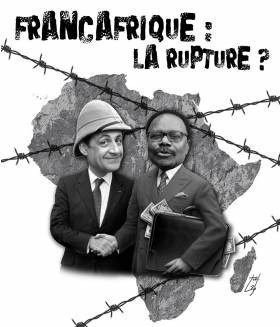

On the other hand, France always had a special relationship with Africa and that relationship persisted even after the end of the Cold War. Between the height of de-colonisation in 1963 and today, France intervened a little more than forty times in Sub-Saharan Africa, more than any other power. It even has a word for its special relationship to its former French colonies – françafrique. Many French countries that gained their independence continued to have privileged relations with France and the self-professed grandé nation had exclusive and often secret defence pacts with numerous African nations.

Global power shifts that come to mark much of the last two decades have cemented France’s role in Africa rather than pushing it into history

During the 1990s, however, the special relationship with Africa was felt to be outdated and the large military footprint was seen more as a liability than an asset. Sure, it provided France with international standing and reputation, but Paris, too, sensed it was time to move on. When Nicolas Sarkozy first ran for presidential office, he promised an end to the françafrique. That promise came shortly after the government led by Jacques Chirac had intervened in the Ivory Coast, where contested results of democratic elections threatened to unravel the tenuous security in the Gulf of Guinea nation. Despite all promises otherwise, France remained an African power.

Ironically, the global power shifts that come to mark much of the last two decades have cemented France’s role in Africa rather than pushing it into history. The rise of the BRICS, and Brazil and India in particular, has created new world leaders willing to take the reigns from Portugal and Britain and these two countries are happy to pass the responsibility for their legacies on. Brazil is already investing heavily in the formerly Portuguese countries, particularly in Angola, and India has long had an intense relationship with the former British colonies in Eastern Africa, cemented by a huge Indian diaspora living along the eastern African coast. One might recall the more controversial time a certain Mahatma Gandhi spent in South Africa. In the francophone sphere, however, there is no natural heir of the French-speaking world. Inadvertently, however, the rise of these emerging powers makes France’s interest in strengthening the influence of francophone countries in Africa more difficult to achieve. And if that would not be bad enough, it is the francophone countries that often have the worst governance record of all African states.

And so, France’s special relationship with Africa persists and, in contrast to other former colonial powers, France still cannot fully escape its African legacy, even it wished to. It still operates a string of bases in Africa, while Paris still has its own garrison in Gabon, the Ivory Coast and even Chad. Though France has occasionally reduced its footprint in Africa, it has strengthened rather than weakened its defence arrangements with countries from Cameroon to Senegal and Togo. And while economic interests are an important factor in some of these African nations, they certainly are not in places like Togo.

Not only because of the ambivalent history of French interventions in Africa, many diplomats from the region realise that in the long run, they cannot trust that the French will always be there to bail them out. At that conference in Benin, most of these African seemed to have realised that now it is the time to develop their own regional mechanisms. At least rhetorically, they are ambitious enough. The divide between ambition and reality is no bigger in Western Africa than it is in Europe and one might find comfort in that.