In the context of the Arab Spring, the use of the term “Islamism” is very common. The new political elites throughout the North Africa, commonly referred to as the “Islamists”, often talk of replacing the old and more or less authoritarian secular regimes in the Middle East. Journalists also use the term quite excessively and I am not sure that they really always know what they are writing about.

It is one of the reasons why the Western public is frightened by the term or at least confused by it. After all, the Islamists are not just known as organizations and political parties which have been increasingly dominating politics in countries affected by the Arab Spring series of uprisings (Muslim Brotherhood, An-Nahda,…), but they are also known as radical followers of Al-Qaeda, various offshoots of Islamic Jihad, the Palestinian Hamas, the Lebanese Hezbollah, the Afghan Taliban, etc. Using the same term for these entities must necessarily have a negative effect on the public’s view of what is happening in the Middle East and especially the consequences of the Arab Spring.

Muslim Brotherhood and since 1928, it has undergone a number of developmental stages, radicalizations and moderations: originally established as a charitable and non-political organization, it has gradually evolved to become politicized and radicalized

The use of the term “Islamism” in general discourse is very vague and often confusing. It is trying to evoke a seemingly clear and unequivocal understanding of a concept which is, in fact, very general – and also has great internal dynamics. After all, even the Islamists in the period before the Arab Spring, who often worked in hiding or at least in opposition to the ruling regime, are not always the same as the Islamists who are represented in the parliaments and government coalitions today – even though the two groups may still carry the same name. The dynamic nature and ambiguity of the term “Islamism” are the most self-evident when one looks closely at the dynamics and ambiguity of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Since 1928, when it was founded, it has undergone a number of developmental stages, radicalizations and moderations: originally established as a charitable and non-political organization, it has gradually evolved to become politicized and radicalized (it even began to organize assassinations of top government officials), later transforming itself into a semi-legal organization with its own political apparatus, which proved to be of a great advantage when it finally decided to join the formal political processes in Egypt in the wake of the Arab Spring.

Importantly, the Islamic understanding of politics is also very different from the Western concept. While in the West there is a relatively clear separation between state and religion, in traditional Muslim society, as in traditional Jewish society, there is no separation of secular and spiritual power – they are intertwined into one. In the context of contemporary world events and attempts at finding parallels between Islam and political radicalism, the term “Islamism” is even vaguer than, for example, the term “Christian politics”. After all, “protecting Christian values through politics” could also have various colors, although it is largely known in the minds of Westerners as something at least “relatively constructive” in the sense of the Christian-democratic parties. Today, it is also not often remembered that the “Christian” politics does not involve just “Christian” democracy, but that it has at times acquired also militant forms (the clerical fascism of Ustasha in Croatia during the Second World War, the conflict in Northern Ireland, Joseph Kony’s “God’s Army”, etc.).

The very understanding of the term “Islamism” and its definition are very ambiguous, and thus the public in the West, the experts, and the Muslims themselves could all have different understandings of it. For the Western public, the concept of “Islamism” has a mostly negative coloring. But the experts warn that the term is so complex and ambiguous that it is difficult for the public to correctly understand it. And Muslims often do not understand the concept the way we understand it at all, since the term “Islamism” is not a traditional Arabic term (like, for example, the terms in the Qur’an), but a Western neologism. Rather than attempting to create yet another definition of “Islamism”, we should stress here two points which are found in its many different definitions: “the Islamic revivalism” and “politicization of Islam”.

Islamic governments have been present in Muslim countries from the very beginning of Islam, with the existence of the Caliphate

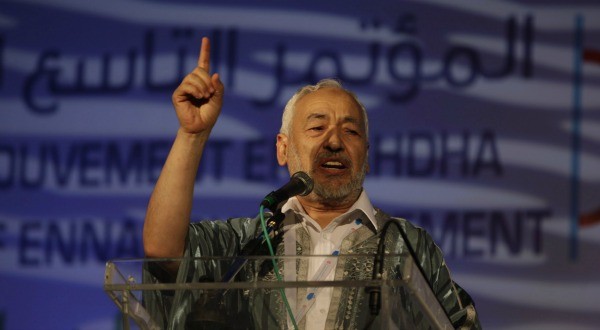

“Islamic Reformation” follows logic similar to that seen in Christianity – a return to the true/original values and to the purity of Islam. The revivalism could often be seen as purifying Islam of the various “sediments” which are considered to be alien and not originally Islamic – such as Sufism and Sufi rituals or cults of saints and pilgrimages to their tombs. But relationship between Sufism and Islamism today is not so clear – even when some Islamist movements clearly reject Sufis, the other Islamist groups could have a mingling of Sufism and revivalism (for example, the Brotherhood’s founder Hassan al-Banna was a Sufi). Then the perception of Islamism as a political project in the sense of the modern understanding of politics does not simply mean an “Islamic government” – Islamic governments have been present in Muslim countries from the very beginning of Islam, with the existence of the Caliphate. It is rather a modern Islamic revival associated with politics – and it can include both parliamentary politics, on the one hand, and radicalism and terror, on the other. As the main spiritual leader of the Tunisian Islamists, Rashid Ghannoushi, proclaimed upon his return to Tunisia from exile after the fall of Bin Ali, “Islam (in Tunisia) is ancient, but the Islamist movement is recent. By [I]slamist movement, I mean the action to renew the comprehension of Islam. I also mean the action which began [at] the end of [the] 70´s and which calls for a return to the sources of Islam, far from the inherited myths and fixation on traditions.”

But we could also find other unifying characteristics of “Islamism”, such as the fact that Islamism is a defensive reaction to Western influence and also that it is a response to “decadent” influences in Muslim societies – to nationalism, to ethnic, tribal, and political fragmentation, etc.). The term “Islamism” also does not reflect in any way how the mentioned values, the commitment to unity, etc. should be achieved. The spectrum is very wide: from participation in politics – e.g. through participation in elections and respecting the constitutionalism streaming from a secular constitution (but for the fundamentalist Muslims the only binding constitution is the Quran) and political competition – through the rejection of democracy as a means of promoting Islamic values to radical anti-system activities which may be associated with the use of violence and terrorism. So if someone still persists in using the term “Islamism”, he should make it at least slightly more accurate by using the terms “moderate Islamism” and “radical Islamism.”

If we follow the blending of Islam and politics in the Middle East – not only during the Arab Spring, but during the past few decades, we can trace several different types of perception of Islamism:

Participative/legal Islamist movements that use constructive and state-building strategies (such as Hizb an-Nahda in post-Ben Ali Tunisia, AKP in Turkey, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, PJD in Morocco)

Radical Islamist/Jihadist movements that use subversive and violent methods for gaining influence and dominance in politics (e.g. Al-Qaeda in Islamic Maghreb, Islamic Jihad).

Hybrid/sui-generis movements that could combine social and charity work together with violent methods (e.g. Hamas in Palestine, Hezbollah in Lebanon), or use radical rhetoric without using violence (e.g. Hizb ut-Tahrir, some Wahhabi streams) or, alternatively, could combine radicalism and social activity with ethnicity (Taliban).

Non-political Islamist movements, such as some Sufi orders and some Salafis, as well as the movement Al-Adl wal Ihsan (“Justice and Charity” in Morocco) and Tablighi Jamaat (an international Islamic missionary movement originating in India) – but whether this is still Islamism, it depends on the circumstances and the specific situation.

Particularly interesting is the last group – the so-called “apolitical Islamists” – which could actually be a contradictory term, because it is believed that one of the main elements of Islamism is at least some effort toward political action. As many followers and leaders of Islamist organizations come from apolitical Islamic movements, these personalities have gone through intellectual developments and shifts. From this perspective, it is interesting to see the recent development in the attitudes among the Egyptian Salafists, who went directly from having apolitical attitudes before the Arab Spring to political participation. Yet, their success and popularity in post-Mubarak Egypt are not as surprising as they might seem at first glance, since it was the Mubarak regime that supported the Salafists as competitors of the much stronger Muslim Brotherhood (using a “divide and conquer” strategy).

Ultimately, we can only hope that, rather than characterizing the phenomenon of “Islamism” – and the blending of political and religious events – in the Middle East and North Africa by simplistic and vague concepts, these will be in the future increasingly described (and criticized) in all of their complexity.