After Algeria’s Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the world has witnessed the fall of Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir on Thursday. Thousands demonstrators in Khartoum chanted and greeted the news that the country’s strongman of three decades had been placed under house arrest.

After Algeria’s Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the world has witnessed the fall of Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir on Thursday. Thousands demonstrators in Khartoum chanted and greeted the news that the country’s strongman of three decades had been placed under house arrest.

Troops have also raided Bashir’s Islamic movement, linked to the ruling party, and deployed at key locations in the capital. Meanwhile, Sudan’s state news agency reported that all the political prisoners in the country were being released. Now what is next for Sudan after coup?

The transition

What’s left of Bashir’s 29-year rule is the military, his militias and his feared National Intelligence and Security Service.

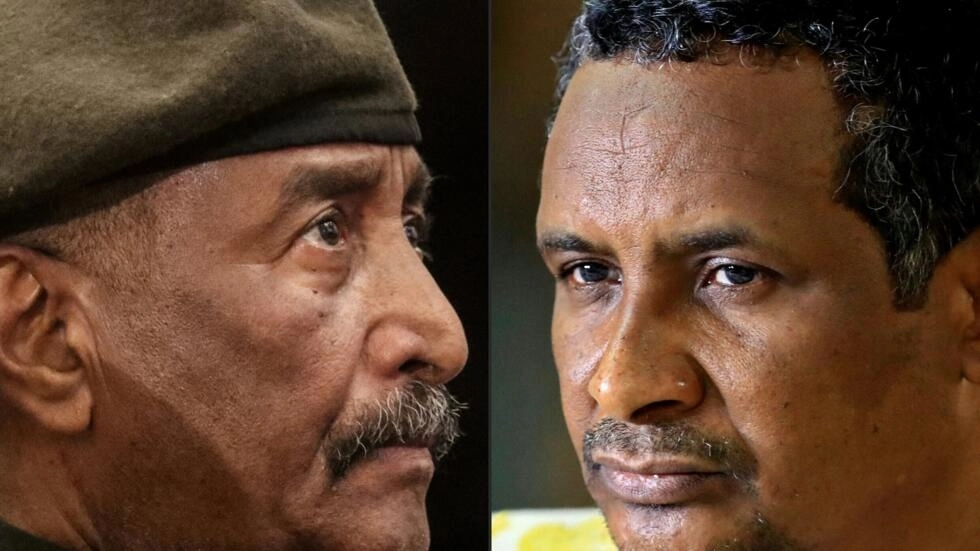

On Thursday, Sudan’s state-run broadcaster said Defense Minister Awad Mohammed Ibn Ouf was sworn in as head of the interim military council that will run the country for two years. The broadcaster said military chief of staff Kamal Abdel-Marouf al-Mahi will be the deputy head of the council.

The protesters celebrated the fall of Bashir, which was the main plank of their movement, started in December, but have rejected what they say is a military takeover.

The Alliance for Freedom and Change group said the new rulers had kept “the same faces”, and urged demonstrators “to continue their sit-in in front of army headquarters and across all regions and in the streets”.

But in recent days, images of soldiers alongside protesters singing, chanting and playing music have circulated on social media. Images of security forces abandoning their uniforms in protest have also surfaced, raising the hope for a bright future for a military-civilian concession.

In response to street protests, the military council on Friday promised the country would have a new civilian government and said it expects the pre-election transition period it announced on Thursday to last two years at most or much less if chaos can be avoided.

The Economy

By 2018 Sudan’s economy was in free-fall, with an inflation rate of 72 percent, long lines at fuel stations and even a shortage of bank notes. The urban middle classes, dismayed to see their living standards collapsing, revolted.

Bashir is wanted by international prosecutors for alleged war crimes in the western Darfur region, and demonstrators accuse him of presiding over years of repression and promoting policies that devastated the economy.

Besides a reign riddled by war, Al-Bashir allegedly looted the impoverished nation of much of its wealth, with leaked US diplomatic cables suggesting $9 billion of his siphoned off wealth has been stashed in overseas bank accounts.

The military council announced Friday that it would not extradite Bashir to face allegations of genocide at the international war crimes court but would brought him before a Sudanese court.

Anyways, analysts expect that al-Bachir’s fall will probably strengthen relations and confidence with investors and Western partners for the take-off of the oil-rich nation economy.