The French-Algerian Relationship: Searching for a New Era

The coming state visit of François Hollande in Algeria by the end of the year is an opportunity to take stock of the political relationship between France and Algeria. For decades, this crucial relationship has been complex, ambiguous and systematically ridden by memories of the bloody and endless war that France imposed on its colony from 1954 to 1962, which was at that time nothing less than a French department.

In a certain way, even 50 years later, there is a fragment of history that is not yet digested and, from both sides, the Independence war – called “Liberation war” in Algeria – still shapes representations and national psyche. For instance, it is only recently that France officially accepted to name the Independence war as a real war, and not as “events” that required operations of policing.

Besides, the Harkis – the Muslims who joined the French army rather than the nationalist FLN – are still considered traitors by the Algerian government. It epitomizes a past that does not pass. It is significant to notice that the first state visit – the highest level of diplomatic contact between the two countries – of a French President Jacques Chirac in Algeria, occurred only in March 2003. Previous official visits were simply working visits, such as those by Giscard d’Estaing (1975) and Mitterrand (1981) in Algeria and Chadli Bendjedid in France in 1982.

The Consequences of France’s Wait-and-See Attitude during the Civil War

The civil war that occurred in Algeria from 1992 to 1998, the national army’s (ANP) opposition to the “GIAs” (Armed Islamists Groups), tore the nation and severely strained the relationship between France and Algeria. During this troubled period, Paris adopted a very cautious position of wait and see that did not meet the expectations of the Algerian government. When the Algerian army intervened in 1991 to stop the electoral process, which would have led to an Islamist’s landslide, François Mitterrand described this interruption as an “abnormal act”, meaning that the democratic process should have been achieved. Algiers’ regime, at that time ruled by the military, coldly greeted this statement that revealed Mitterrand’s ambiguous position: on the one hand, he called for democratization in Africa (La Baule’s speech, 1990); yet, on the other hand, he kept his support for dictators who embodied the dark relationship that France has maintained with its former colonies since De Gaulle.

It is a euphemism to write that Mitterrand, the man who declared in 1954, at the beginning of the Algerian revolution, that “Algeria, this is France”, was not really appreciated in Algeria and this is from this point that the bilateral relationship has seriously distended. Hijacking and hostage-taking of an Airbus at the airport of Marignanne (near Marseille) in December 1994, then the wave of attacks that occurred in France between July and October 1995, both committed by GIA members further increased the tension between France and Algeria. In this context, Jacques Chirac who became president in 1995, known as a Gaullist and thus inclined to renew with the De Gaulle pro-Arab countries foreign policy, was initially welcomed by Algiers. But the “who kills who” controversy maintained by a few intellectuals and French officials when the massacres perpetrated in Algeria redoubled in violence, a tougher right-wing immigration policy against Algerians and the assassination of the French Tibherine monks in 1996 further widened the gap and boosted a mutual distrust. Therefore, Algiers preferred to turn to more reliable and strategic partners, and France must cede ground to the Americans – eager to contain the growing threat of Islamist terrorism they tragically suffered on their own ground in 1993 and abroad in 1998 at Nairobi and Dar Es Salam, but also to the Chinese who began to penetrate the continent.

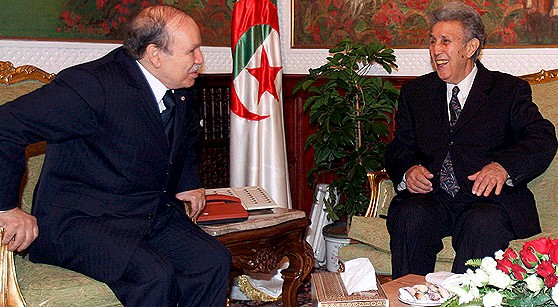

Bouteflika’s Short Idyll with Jacques Chirac

The election of Abdelaziz Bouteflika in 1999, a henchman of the Boumediene’s regime in the 1970s but who left the country after Chadli’s designation, was not really a surprise given that generals backed his candidacy. The national reconciliation policy he immediately implemented brought about peace in Algeria (not without troubles) and finally ended the civil war. Bouteflika’s desire to break with his predecessors and usher in a new era has also materialized in foreign affairs by attempting to renew with the golden age of the Algerian diplomacy he personally embodied under Boumediene.

His effort to rehabilitate the very tarnished image of Algeria after a decade of terrorism passed through normalization with France. He could find in Jacques Chirac the partner he needed to reach that purpose. In all respects, the State visit of Jacques Chirac in Algeria in 2003 was the visible climax of this idyll. Furthermore, it brought about the initiative of a Franco-Algerian Treaty of Friendship that was seriously questioned only two years later when the French Parliament (ruled at that period by a right-wing majority) voted a law whose Article 4 described as “positive” the effects of colonization. Even though the Constitutional Council (an almost Supreme Court) abrogated the contentious article, it torpedoed the whole process of reconciliation.

It is not a secret that Bouteflika never liked Nicolas Sarkozy very much. Being seen as Atlanticist and too liberal, the new president’s personality as well as his ideas regarding Algeria contrasted with his predecessor’s. Partly because of his generation (he did not fight during the war against Algeria) and basically because he has never shown a specific interest in the Arab world, Sarkozy’s attitude towards Algeria was imbued with indifference. On the other side, Bouteflika also greeted with a certain dose of mistrust the new elected president, who was more inclined to strengthen France’s relationship with the United States and, among the Arab States, Qatar or the UAE, rather than turn to the Maghreb.

Sarkozy’s attempt in 2008 to launch a stillborn Union for Mediterranean (UPM), gathering nothing less than 43 states including Israel and Palestine, crashed a few months later when Israel bombed Gaza, sounding the death knell for hopes of peace and reconciliation in this troubled area. At the same time, as a consequence of Sarkozy’s immigration policy and verbal provocations, Bouteflika hardened his position on the question of France’s repentance for colonization. One year later, the so-called “Arab Spring”, whose scope and repercussions were never relevantly measured either by Bouteflika or Sarkozy, definitely buried a “Union” that never overcame its internal deficiencies.

France Remains Algeria’s First Economic Partner: For How Long?

The fact that France and Algeria did not succeed in tackling the past and are still going ahead must not conceal the existing strong economic relationship. For a while, indeed, France has been the first supplier of Algeria and remains the first investor in the country. After a serious slump in the 1990s, because of France’s ambiguous attitude during the Algerian civil war, the economic relationship normalized immediately the internal strife subsided. Supplanted by the Americans a decade ago, the French hydrocarbon’s major Total regained its market share. The big French companies, especially banks such as BNP-Paribas and Société Générale who have been entrenched in Algeria for a decade, are developing and diversifying their activities thanks to a more flexible legislation. The Parisian metro-operator, RATP, now operates Algiers’ new subway that has been built by Alstom. Strangled on their domestic markets and in Europe, French companies are eager to expand in North Africa where they can penetrate close, large and easy markets.

A Fragile but Hotly Competed Market

With a population of 35 million people, Algeria is by far the largest market in North Africa. Its growth potential is huge despite the long-term heavy sequels of the civil war. In October 2013, the announcement that Algeria is taking part in the loan floated by the IMF with 5 billion dollars symbolizes what has been accomplished since 1993-94 when Algeria was forced to negotiate Stand-By Arrangements with the IMF and a debt-rescheduling package with the Paris-Club group of creditors. It also reflects the growing financial capacity of Algeria and its ability to play a key role in the Mediterranean, North-African and even sub-Saharan Africa.

Algeria has dramatically increased its foreign currency reserves (now around 180 billion dollars) due to its strong hydrocarbon revenues. Therefore, in 2011, the Algeria sovereign fund, replenished by these revenues, culminated at 57 billion dollars. However, this must not hide certain weaknesses. Algeria seems still to hesitate between, on the one hand, the continuing liberalization of its economy, free-trade and compliance with the international norms that rule the financial sector, and, on the other hand, a sort of State-capitalism that grants the government a major role in all sectors of economy.

The “49/51%” ownership rule, which requires a 51% Algerian share in foreign direct investments, is considered as an obstacle by many foreign investors, even though it did not prevent a lot of foreign companies from moving into Algeria. Then, the government’s efforts to diversify the economy from hydrocarbons, which are still the backbone of the economy, have not yet produced much effect. Finally, the explosive social situation characterized by massive youth unemployment and huge housing demand that provoked sporadic riots, captures recurring public grants (more than 23 billion in 2011) and highlights the lack of redistribution.

Even though the domestic situation remains fragile, Algeria’s wealth gives the country the ability to choose its partners. Algeria does not want to depend economically on only one partner anymore, and particularly France, with whom it has had tumultuous political relations. Algeria’s market size and the business opportunities that exist there stir up the appetites. Over the last decade, the foreign investors coming from Southern Europe or Turkey have flourished. The Arabs, like the Egyptian telecom company Orascom with Djezzy or Gulf Bank, came very early on, in the late 1990s, when the security was not provided throughout but new president Bouteflika encouraged foreign investment.

Nevertheless, China is now the most important and growing foreign investor in Algeria. China that ranked second behind France (but first by some months) contributes to the funding of most major projects and leads the construction boom: the country’s largest prison, a new airport, malls, thousands of homes, etc. A Chinese state company is building two-thirds of Algeria’s 745-miles-long east-west highway, which is the longest in Africa. All that represents around 20 billion dollars in government construction contracts. China’s role in Algeria is now most significant since Mao supported the newly independent country all along the 1960s. Very recently and after protracted negotiations, the Chinese company HNA bought 48% stake in Paris-based airline Aigle Azur that holds 43% market share in Algeria.

A Cloudy Future?

According to many Algerian entrepreneurs and policy-makers, France is no more the adequate partner nowadays. French companies are known to be ‘chilly’ compared with Americans, Chinese or Turks that are all more pragmatic. Moreover, many Algerians do not understand why the French do not use much more of the resources of the Algerian diaspora in France. Through immigration and television, Algerians are strongly connected to what happens in France, to the French politics and the recurrent Algeria- or Islam-related issues that occur in the public debates.

This distrust climbed up to an acme during the Sarkozy’s mandate. It points out how politics and history still permeate and deform the whole French-Algerian relationship and how they impact the economic field. Nothing can be simple with the Algerians, think the French, and the Algerians share exactly the same feeling. It will last until a new dispassionate era is launched in the relations between these two states. Devoid of negative effects with Algeria, François Hollande may be the man who can usher the relationship into the new era. However, the future is cloudy because Bouteflika is ill and his succession far from obvious, but also because no one knows how François Hollande will understand and handle the French-Algerian relationship. New appointment in Algiers is expected in December.